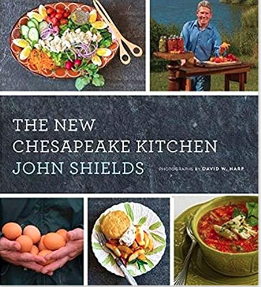

My autographed copy of The New Chesapeake Kitchen is embellished with a loopy but earnest note: “Let’s cook the bay and body-friendly way. Best Fishes! John Shields.”

The author—a groundbreaking chef, serial restaurateur, and television host—is globally acknowledged as the authority on Chesapeake cuisine, as well as a leader for environmental causes pertaining to foodways, health, and economic justice. Many know him simply as John, a man with a contagious smile who cannot resist a corny joke or a conversation.

In 1990, decades before Maryland restaurants prioritized farm-to-table eating and locavore mores, Shields published the original Chesapeake Bay Cookbook, extolling the virtues of eating seasonal food grown locally, as well as strategically supporting Maryland-based watermen, farmers, and small businesses through meals that high- light the region’s bounty and cooking style.

“Chesapeake cuisine is a sense of place, of being rooted here,” he explains in an interview, describing the largest estuary in North America and its thousands of tributaries and creeks, with a climate that varies from the Appalachians to the Atlantic Ocean, as a teeming protein factory. According to Shields, Chesapeake cooking is about utilizing the freshest regional foods available and treating them simply and reverently to let those flavors come through.

For regulars at Gertrude’s, now a twenty-year mainstay at the Baltimore Museum of Art, the chef’s regard for the Chesapeake as a source of culinary abundance is a given. As is his reverence for the legendary crab cake and the namesake for his restaurant: his grandmother, Gertie Cleary, a Baltimore native whose Waverly home was the site of Shields’ earliest cooking experiences.

Shields is the product of a family steeped in Maryland food traditions, including farmers, vendors in the North Avenue and Lexington markets, and a great uncle who ran a seafood packing plant on Tilghman Island. However, a sense of natural curiosity led him far from Baltimore, to influential centers of culinary culture in the 1980s and ’90s, molding him into a visionary leader. Linking food tradition to environmental stewardship and innovative nutritional practices to a specific region, this movement has quietly and steadily influenced Baltimore’s entire food ecosystem for the better.

Shields started out hellbent on a career in music. After a brief stint at the Peabody Conservatory, he hitchhiked to Provincetown in the summer of 1972 to perform and party with John Waters’ Dreamlanders. Provincetown was then a Portuguese-American fishing village full of seafood restaurants hiring seasonal help (the proving ground for another globally recognized chef, author, and food celebrity: Anthony Bourdain).

It was also a burgeoning gay vacation destination, an added bonus for Shields, who was raised Irish Catholic in Parkville. He played piano in bars, but realized that “Rock stardom is not easy to come by in the winter in P-town,” and found himself working in the kitchen at the Provincetown End, then the largest resort in New England. This led to subsequent forays into various seafood gigs, as well as New York restaurants, bouncing between the two cities for several years.

In 1978, Shields moved to California with his then-boyfriend, John Kelly, and began working at A La Carte, a tiny French restaurant in Berkeley, where he designed and executed a changing daily menu after chef Jonathan Waxman left to open a restaurant in Los Angeles. Shields began each morning at five, shopping for fresh ingredients at farmer’s markets in Oakland and Chinatown.

“It was the most amazing culinary exercise,” he says. “I read French cookbooks day and night. All the winemakers from Northern California would come and I’d design menus for their tastings there. Frank Prial, the wine critic from the New York Times, would often dine there.”

Shields found himself at the center of the “gourmet ghetto” of Berkeley, a community of chefs including Alice Waters, Bradley Ogden, Bruce Aidells, and Jeremiah Tower, all pioneers who revolutionized American food entirely. When investors approached about opening a bigger place, Shields jumped at the offer, designing a menu based on the food he grew up with and opening Gertie’s Chesapeake Bay Cafe in 1983.

After five years, Shields sold Gertie’s and operated a San Francisco Bay take on a Lower East Side Jewish deli. Kelly—no longer his boyfriend but still a business partner—helped source authentic ingredients from his hometown of New York. Here, Shields met a publisher from Aris Books who suggested he create a Chesapeake cookbook because there was no national definitive text on the subject.

Shields took a yearlong sabbatical and traveled the Chesapeake region in a Volkswagen bug, collecting stories from farmers, watermen, and their wives in church halls and firehouses. Combining anthropological research, Maryland history, environmental issues, and family tradition, Shields published The Chesapeake Bay Cookbook: Rediscovering The Pleasures of A Great Regional Cuisine in 1990—a readable tome peppered with quirky anecdotes and photos of the individuals who inspired the recipes.After a few years of touring and promotion, Shields became a regular radio and public television personality. During the ‘90s, Shields’ success was bitterly tempered by the AIDS epidemic, centered in the San Francisco Bay area, and he spent several years caring for sick friends, including Kelly, who passed away in 1993. That Thanksgiving, Shields was emotionally and physically spent, and instead of hosting his usual “friendsgiving” extravaganza, he volunteered at a soup kitchen. That day Shields met his future husband John Gilligan, a social worker originally from Chicago.

In 1998, the 13-part series Chesapeake Bay Cooking with John Shields debuted on PBS. That year, Shields and Gilligan returned to Baltimore and opened Gertrude’s Restaurant at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

“We looked at a bunch of spots and city officials were trying to get us to open in the Inner Harbor, but I wanted something with more cachet, also off the beaten path,” he says. “And when we saw the BMA sculpture garden, it was such a beautiful space, so we decided to go for it.”

“It was difficult at first because people did not think of fine dining at a museum,” Shields explains. “We were the first restaurant in the United States to do this, but it attracted articles in all kinds of travel and leisure magazines, and started a whole movement of restaurants in museums.”

From the very start, it was important to Shields that the menu change with the seasons to serve whatever was fresh—common in the California restaurants he trained at in the ‘80s, but still somewhat unconventional in the ‘90s elsewhere.

In Berkeley, Shields knew all the people who grew his food: the farmers and the mushroom foragers, local fishermen, and the opera singer who raised his quail. But in Baltimore, there was no network for farm-to-table restaurants, so he sought it out—first finding David Smith from Springfield Farm, as well as his own cousins who were still farming. “I went to the farmer’s market every week, and that was crucial to build relationships with them to source the products I wanted, and this is still what I do now.” Although Shields does not source all the ingredients needed to operate a restaurant from the Chesapeake, he purchases everything that is in season from local farmers.

“It’s an interesting place, being in a museum, because we have to accommodate visitors from all over the world and from every socioeconomic background,” he explains. “I didn’t want it to be something that was too pretentious or intimidated people. It was very important for me to make it a welcoming spot for everybody, which is such a Baltimore thing.”

For the past decade of his personal cooking life, Shields has preferred plant-based foods for health and environmental reasons, and found Diet for a New America by John Robbins inspiring. Reading about the environmental impact of meat and poultry, particularly in the Chesapeake region, led to more plant-based options on the menu at Gertrude’s.

“The Bay as we know it today has changed,” he writes. “There are many seafood varieties that were once plentiful, but are now either completely gone or in danger of collapse, and invasive species disrupting the biodiversity of the Bay.”

Shields explains that the human population in the region has soared, putting undue stress on the natural environment. Concentrated factory farming and animal production pollute the waterways and groundwater—all diminishing the water quality of the Chesapeake. Despite the myriad problems we face in this region, Shields insists the new book is really about hope.

“It’s about the future of the Bay. It tells the tales of the heroes, dreamers, and visionaries who love the Bay,” he says. In addition to recipes, Shields focuses on the oyster farmers revitalizing an industry and restoring water quality, small nonprofits utilizing invasive species, and a new generation of farmers operating with care for animals and in harmony with the environment. Shields strives to spread awareness of the farmers, biologists, and environmentalists restoring the Bay and the watershed’s soil, and rebuilding a local food economy.

Shields explains that the human population in the region has soared, putting undue stress on the natural environment. Concentrated factory farming and animal production pollute the waterways and groundwater—all diminishing the water quality of the Chesapeake. Despite the myriad problems we face in this region, Shields insists the new book is really about hope.